“The first obligation of an art critic is to deliver value judgements.”

--Clement Greenberg

A great controversy ensued, where the friends and supporters of Ms. Favaretto protested against the possible ‘borrowing’ of their artist friend’s idea and came to a point of pulling out such work in the ongoing Art Basel Fair. The works were pulled out and Allora and Calzadilla were banned in joining future exhibitions.

However, after this seemingly critical decision on the part of the organizer, the artist herself, Lara Favaretto came forward, and finally had broken her silence about the issue.

She invoked the dogma of Alighiero e Boetti that encourages the artist to disseminate ideas as freely and widely as possible.

At the end, the two Puerto Rican artists were compeled to argue that there is nothing new about turning table into a boat. In fact, when researching their project, they discovered that there are numerous examples of floating tables, all made by individuals who are not artists, and all of which predate, some by decades, the work of Favaretto’s version.

As an artist myself, there are a few lessons to learn from this story, some philosophical and others quite down to earth. In my opinion, these events provide a clear picture of how art, despite its increasing value, remains an unregulated commodity, leaving artists’ ideas vulnerable to potentially unethical appropriation.

But if in case there is more conceptual basis for such incredible resemblance between artists’ works to consider, I for one would still argue that such appropriative artistic practice is not excatly original. On the other hand, if one would take the like of Maurizio Cattelan, for example, has been doing something similar for most of his career; but in his case the appropriation is his declared goal, and so many artists like him were and still are using other artists’ ideas for their own works.

Perhaps a more interesting dialogue would consider how the same form can be used by unrelated artists to radically divergent ends.

But what if, the appropriated work is a cultural object or cultural symbol from a culturally diverse community? Would it draw controversy, or worse, a violent reaction? These probable incidents were carefully weighted upon in the deliberation prior to the Sambolayang Project.

As Mother Romy would often castigate us in the K.E Alumni, to be original and be very carefull in ‘borrowing’ cultural ideas, and most of the time he frowns upon us of creating works without proper research, background, or source.

The Sambolyang Project was tasked to me to conceptualize and implement, but it came as a germ of an idea by Mother Romy in 2003 after a lengthy discussion in our house at Buayan. Mother asked if it is possible to make a painting on a ‘sambolayang’, and I explained that in the visual arts, any object or material can be used as a ‘canvas’ provided it can absorb painting medium. I even included using ‘pasandalan’. Mother exclaimed that that idea is’very original’. And so it is.

No artist would claim that his work is not original and unique, for we attain the highest standard of our career because of the seemingly original and novel conceptions we create. We artist strive to such end. But are our ideas just pop out without a considerable influence of our experiences, readings, and exposures?

I think not, for our ideas to become great and distinguised must undergo a certain degree of a poweful sway and influence from the many things stored in our minds.

To make the sambolayang as canvas is no longer unique, for flags, heralds, tapestries, or even walls, building facades, rooftops, and countless many things are used as medium of painting surface. Perhaps the only original in its idea is because it is done on a sambolayang, period.

Mother Romy reiterated that because it is a new conception, we must implement such project sooner or fear of losing it by appropriation by other artists and lose its originality. It took us four years since its conception as an idea to realize as a project. And thanks to the ACT for Peace Programme, the Sambolayang Project was finally initiated.

But what is a sambolayang? Why we intend to make it as a project?

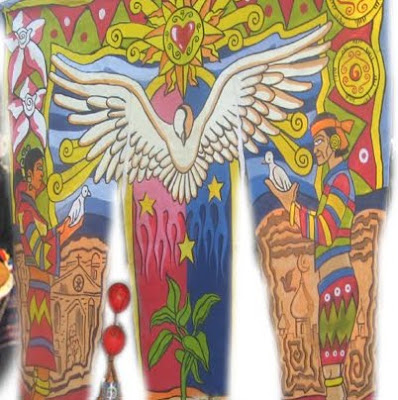

The sambolayang—is a large type of tapestry with the sole purpose in an outdoor hanging with a horizontal pole attach to it suspended on a vertical long pole. The immense cloth is rectagular where the length is vertical and the lower portion having three triangular fork like cuts dangling, with tasles serving as deadweights.

History would suggest that the same three-forked flag is not purely endemic in Mindanao, but were already used in Imperial China, Empire of Kambuja, Thai Kingdom, Kingdoms in Java and Sumatra and the Malay and Bornean kingdoms. Colorful flags and banners were used in both festivals and wars in these areas as signifying one rank and clan. Imperial crests and noble heralds were produced as standard coat of arms of one ruling clan or a vassal family. These heralds were to proclaim such noble lineage and the extent of its influence and power.

On the other hand, display of flags and banners would suggest a festivity or an act of war.

Mindanao sultanates have no record of using coat of arms that has survived, but the used of an elaborate display of colorful awnings, banners, flaglettes, tapestries, hanging tiered-parasols, large vertical flags, and the three-forked tapestry are still used in two major cultural events such as wedding and noble coronation.

These colorful displays of flags and banners are to signify as ‘tous’—or landmarks of such fanfare and celebration. Flaglettes—pandji—along the roads would become markers giving direction to where the festivity is located, and large flags—pasandalan—would become familiar sight of attraction. But an immense sign post is usually above any house, fluttering in the wind, the sambolayang—the pointer of the greatness and noble of such festival and the grandness of the occasion. Its uses became very exclusive among the members of the nobility and it became a symbol anything than the power of the lords of the land to wield absolute power over its people.

But time passes and for generations the absolute power of the ruling class waned, and came to realize that the power does not come from the nobility, but from the people who supports it: In Maguindanao, then ‘Lutao’—sea mariners were important in its development as a center of trade and later power in Mindanao; sea warriors of Sulu who fought and gained Borneo for the Sultan of Sulu; and the farmers along the delta of the inundated Pulangi river that made the Ancient House of Buayan the paramount lord of Mindanao before Kudarat, and around the Lanao Lake that helped established the four Royal Houses of Ranao.

Intermarriages and alliances were made from time to time among ruling houses to ensure its influence and survival, and the people were there to support such connections and coalition among the ruling families.

Because of this, the symbol of the ruling elites shifted from exclusively within to comprehensively outside—its many coalition, association, and interconnection. The festivals were made no longer as the promotion of the power of the nobles, but the promotion of the importance of the people, a gathering instituted to strenghtened the bond between the ruling class and the constituency.

The pageantries and the festivities conducted annually were not only for pomposity and spectacle, of entertainment and amusement for the populace, but a very significant gathering for socialization and interaction among the varied supporters of the ruling elites intensifying more of their allegiance and escalating the connection between them, the rulers and the ruled.

In the end, the rulers were not only seen as the absolute sovereigns, but as the representative of the people, their protectors, as well as their benefactors.

Grand weddings, coronations, a baptismal, or the celebration of the ‘moulud’—birthday of the Prophet, or even in the celebration of the Hariraya Puasa—the breaking of the Ramadan, became an assemblies of the people both noble and common, showing off the solidarity that strenghtened their existence as people—eating together, praying in congregation, discussing issues, and sometimes resolving problems and ending conflicts.

Out of these social interactions, the ruling leaderships can sway and influence the support of the people in both times of peace and in war.

The colorful landmarks hence became the symbol of this meeting of the upper and lower segments of Moro society showcasing its power and strength through this bond of solidarity and shared aims. The sambolayang, though it retained its exclusivity of used for the nobility, its sole purpose was to recognize such grand gathering of the varied segments of society where everyone’s support was needed. The sambolayang became a very important marker that proclaims such unity and harmony.

Using such premise, our resolve to use the sambolayang as part of our desire to promote peace through arts was strengthened. We saw that by using the power of its message—a landmark and attraction—we can also advance our advocacy of peace, and somehow cross boundaries and reach multitudes. The sambolayang would become our landmark and signpost of peacemaking in this part of Mindanao. A milestone of peace initiative through the arts using the sambolayang as marker—‘tous’—that would initiate gathering among the various segments of society creating important discussion and dialogue in the process.

But let us make clear that our intention was never to engage in some diabolical act of artistic theft or desecrating a cultural symbol to suit our ends.

Rather, our motivations stemmed from the desire to make metaphoric statement,

like the table-cum-boat, a vehicle, or a tool striking enough to stimulate discussion around the complex issues concerning peace and unpeace, its effect and consequences; and like in the case of the story of the table-cum-boat, presenting a discussion on the issue of a historic contested space that triggered the land-reclamation movement on the island of Vieques, Puerto Rico in the 1970s.

It was an ethical imperative for justice and peace sustainability that sparked our imaginations.

Ultimately, then, we wished to raise questions about the terms of the negotiation for peace, asking who is counted in this debate and who is excluded.

Our intention at the very start was very clear: create a peace initiative using the power of arts to relay the message of peace. Nothing more, nothing less. And speaking of the arts, the contemporary visual arts was chosen as medium of this expression.

In contemporary visual art, any object, entity, or article, however mundane or trivial, symbolic or religious, social or political significant can be used as means for creative artistic works—and most often the more shocking and controversial, the better. In painting, any surface can be utilized—even the sambolayang.

We were not there to shock the sensibilities of the Moro people. We were just appropriating the symbol as landmark and mark of attraction of the sambolayang. We were just appropriating its ‘form’ and the communication of its substance.

If in the process, there were and still are find this project very controversial and shocking to their sensibilities, these we cannot stop nor do about. We respect with utmost humility their freedom to exercise such reaction, as such we are to be respected with our expression with utmost understanding. We welcome criticisms as well as constructive evaluation for it is most needed to the assessment of success of our endeavor. A little controversy stirs up people to talk about us, and what we want to convey, and in the process adds to the relaying of our message.

As a member of a South branch of Maguindanao living in General Santos City, I would still be using whatever cultural symbol or material culture that we have, in order for me to promote my message of advocacy to social issues and concerns. Although I could no longer preserve them, I would do a greater service to its somewhat preservation by putting them in another context of importance.

As a visual artist, I would still continue my role as an artist—fighting for the freedom of expression and spread my advocacy of social issues within my community in particular, and society in general.

And if in the future, some artists might happen to appropriate some or portion of my works, and so be it for according to the dogma of Alighiero e Boetti, we as artistse’ must always encourage other artists and ourselves to disseminate ideas as freely and widely as possible. Salam!